Synthesia is your piano tutor. Sharp notation, Windows 10 MIDI, 'Simple' labels, AVI export, and more! Sheet music now always appears sharp, regardless of size.

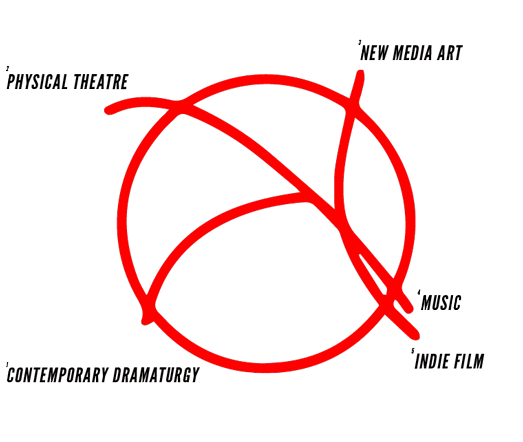

Cover Story

Cite this- Synesthesia glasses The Synesthesia Glasses are an experimental sensory manipulation tool that allow the wearer to experience what it might be like to have synesthesia. By cross feeding the sonic and visual senses, using augmented reality technology, the glasses create a hallucinatory experience.

- Dec 27, 2017 Powerful, midi mappable controls over visual effects. Import your own images and videos to transform with shaders. Shader importing to add fresh content to your Scene Library. Syphon support to integrate with any other VJ software. Creates real-time video output to send directly to a projector. SYNESTHESIA COMMUNITY.

Guitar music doesn't just tickle Carol Crane's fancy--it also brushes softly against her ankles. When she hears violins, she also feels them on her face. Trumpets make themselves known on the back of her neck.

In addition to feeling the sounds of musical instruments on her body, Crane sees letters and numbers in brilliant hues. And for her, units of time each have their own shape: She sees the months of the year as the cars on a ferris wheel, with July at the top, December at the bottom.

Sean Day, PhD, tastes in technicolor.

'The taste of beef, such as a steak, produces a rich blue,' says Day, a linguistics professor at National Central University in Taiwan. 'Mango sherbet appears as a wall of lime green with thin wavy strips of cherry red. Steamed gingered squid produces a large glob of bright orange foam, about four feet away, directly in front of me.'

Crane and Day share an extraordinary sensory condition called synesthesia.

The phenomenon--its name derives from the Greek, meaning 'to perceive together'--comes in many varieties. Some synesthetes hear, smell, taste or feel pain in color. Others taste shapes, and still others perceive written digits, letters and words in color. Some, who possess what researchers call 'conceptual synesthesia,' see abstract concepts, such as units of time or mathematical operations, as shapes projected either internally or in the space around them. And many synesthetes experience more than one form of the condition.

The condition is not well known, in part because many synesthetes fear ridicule for their unusual ability. Often, people with synesthesia describe having been driven to silence after being derided in childhood for describing sensory connections that they had not realized were atypical.

For scientists, synesthesia presents an intriguing problem. Studies have confirmed that the phenomenon is biological, automatic and apparently unlearned, distinct from both hallucination and metaphor. The condition runs in families and is more common among women than men, researchers now know. But until recently, researchers could only speculate about the causes of synesthesia.

Now, however, modern behavioral, brain-imaging and molecular genetic tools hold exciting promise for uncovering the mechanisms that drive synesthesia--and, researchers hope, for better understanding how the brain normally organizes perception and cognition.

Synesthesia Live Visual Software App

Research suggests that about one in 2,000 people are synesthetes, and some experts suspect that as many as one in 300 people have some variation of the condition. The writer Vladimir Nabokov was reputedly a synesthete, as were the composer Olivier Messiaen and the physicist Richard Feynman.

The most common form of synesthesia, researchers believe, is colored hearing: sounds, music or voices seen as colors. Most synesthetes report that they see such sounds internally, in 'the mind's eye.' Only a minority, like Day, see visions as if projected outside the body, usually within arm's reach.

Some synesthetes report experiencing sensory overload, becoming exhausted from so much stimulation. But usually the condition is not a problem--indeed, most synesthetes treasure what they consider a bonus sense.

'If you ask synesthetes if they'd wish to be rid of it, they almost always say no,' says Simon Baron-Cohen, PhD, who studies synesthesia at the University of Cambridge. 'For them, it feels like that's what normal experience is like. To have that taken away would make them feel like they were being deprived of one sense.'

Scientific milestones

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, synesthesia enjoyed a flurry of scientific study, mostly descriptive. By the mid-20th century, however, synesthesia had fallen off scientists' radar, a casualty of the behaviorism movement. The phenomenon began to resurface as a subject of psychological inquiry beginning in the 1970s, stimulated largely by the work of two scientists.

In 1975, Yale University psychologist Larry Marks, PhD, authored a review of the early history of synesthesia research in the journal Psychological Bulletin (Vol. 82, No. 3), the first major psychological treatment of the subject after a 30-year drought. Then, in the early 1980s, neurologist Richard E. Cytowic, MD, published several case reports of synesthesia. He proposed, provocatively, that the condition's cause rests in the limbic system, a more emotional and 'primitive' part of the brain than the neocortex, where higher order thinking occurs. Although that theory has not received widespread support, Cytowic's case studies and his popular 1993 book, 'The Man Who Tasted Shapes,' heightened synesthesia's prominence and prompted psychologists and neuroscientists to examine the condition experimentally.

Synesthesia Live Visual Software Studio

In 1987, a team led by Baron-Cohen found the first hard evidence that synesthetes' experiences are consistent across time. The researchers asked a synesthete to describe the color that each of 100 words triggered. A year later, they repeated the test without warning and found that the associations between words and colors that their subject described were consistent with her initial responses more than 90 percent of the time. In contrast, people without synesthesia, asked to perform the same task but with only a two-week interval between the two tests, were consistent only 20 percent of the time.

In later research, Baron-Cohen's group established that synesthesia is not only consistent across time but also concretely measurable in the brain. Using positron-emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging, the researchers have found that for synesthetes who report colored hearing, visual areas of the brain show increased activation in response to sound. That isn't the case for nonsynesthetes.

Other studies have demonstrated that synesthetic perception occurs involuntarily and interferes with ordinary perception. And last summer, University of Waterloo researchers Mike Dixon, PhD, Daniel Smilek, Cera Cudahy and Philip Merikle, PhD, showed that, for one synesthete, the color experiences associated with digits could be induced even if the digits themselves were never presented. These researchers presented a synesthete with simple arithmetic problems such as '5 + 2.' Their experiment showed that solving this arithmetic problem activated the concept of 7, leading their synesthete to perceive the color associated with 7.

This finding, published last July in the journal Nature (Vol. 406), was, according to Dixon, the first objective evidence that synesthetic experiences could be elicited by activating only the concepts of digits. As such, these results suggest that, at least for this synesthete, the color experiences were associated with the digit's meaning, not just its form.

Together, the evidence shows that 'something is going on in the sensory areas of the brain,' concludes Christopher Lovelace, PhD, a research fellow at Wake Forest University School of Medicine. 'What we have to do now is try to figure out how the brain does it.'

Uncertain origin

A century ago, researchers ascribed synesthesia, somewhat vaguely, to 'crossed wires' in the brain. Today, despite neuroscientists' more complex understanding of brain anatomy and their sophisticated tools for tracking brain function, synesthesia's roots continue to elude understanding. Several competing theories have emerged, but all require further testing. Latest apple mac update.

Baron-Cohen and his colleagues propose that synesthesia results from a genetically driven overabundance of neural connections in the brain. Ordinarily, Baron-Cohen explains, different sensory functions are assigned to separate modules in the brain, with limited communication between them. In synesthesia, Baron-Cohen and his colleagues posit, the brain's architecture is different. Synesthetes' brains, they believe, are equipped with more connections between neurons, causing the usual modularity to break down and giving rise to synesthesia.

Daphne Maurer, PhD, a psychologist at McMaster University, has further speculated that all humans may be born with the neural connections that allow synesthesia, but that most of us lose those connections as we grow.

Naropa University psychologist Peter Grossenbacher, PhD, agrees that there's likely a genetic root to synesthesia, and like Baron-Cohen's group, he and his colleagues have teamed with molecular geneticists to probe the question. But Grossenbacher and his colleagues suspect a different brain mechanism.

'We don't need to posit some abnormal architecture of connections in order to account for synesthesia,' Grossenbacher argues.

Instead, he proposes that in the brains of synesthetes, 'feed-backward' connections that carry information from high-level multisensory areas of the brain back to single-sense areas are not properly inhibited. Ordinarily, information processed in such multisensory areas is allowed to return only to its appropriate single-sense area. But in synesthetes' brains, Grossenbacher argues, that inhibition is disrupted somehow, allowing the different senses to become jumbled.

Grossenbacher believes his view is consistent with the fact that hallucinogenic drugs can temporarily induce synesthesia.

'I don't think that new connections are forming in the brains of those individuals for a few hours and then disappearing,' he says. 'What's much more sensible is that existing connections become used in a way that's neurochemically altered for a few hours.'

But, Grossenbacher acknowledges, 'The trouble with theorizing in this area is that we're underconstrained by data. There isn't the right kind of data, yet, to differentiate between these different theories.'

Baron-Cohen agrees, 'Neuroimaging is the best thing we've got at the moment, but the spatial resolution isn't good enough to allow us to see whether the individual connections in the brain are cross-wired.'

Post-mortem examinations would allow closer inspection of what's different about synesthetes' brains, Grossenbacher and Baron-Cohen agree. But, so far, no known synesthetes have died and left their brains to science.

Implications

For psychologists, interest in synesthesia extends far beyond just the study of the few individuals who experience the phenomenon.

'Synesthesia taps into a lot of other domains that are more familiar to many psychologists,' says Marks. 'It tells us something about the nature of perception and what makes things perceptually similar to one another. Video editing software free. download full version no watermark. Synesthesia may help us to understand how the concept of similarity is embedded within the nervous system.'

In addition, Dixon suggests, the fact that synesthetic perception interferes with the perception of physical stimuli highlights an important aspect of cognition.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, synesthesia enjoyed a flurry of scientific study, mostly descriptive. By the mid-20th century, however, synesthesia had fallen off scientists' radar, a casualty of the behaviorism movement. The phenomenon began to resurface as a subject of psychological inquiry beginning in the 1970s, stimulated largely by the work of two scientists.

In 1975, Yale University psychologist Larry Marks, PhD, authored a review of the early history of synesthesia research in the journal Psychological Bulletin (Vol. 82, No. 3), the first major psychological treatment of the subject after a 30-year drought. Then, in the early 1980s, neurologist Richard E. Cytowic, MD, published several case reports of synesthesia. He proposed, provocatively, that the condition's cause rests in the limbic system, a more emotional and 'primitive' part of the brain than the neocortex, where higher order thinking occurs. Although that theory has not received widespread support, Cytowic's case studies and his popular 1993 book, 'The Man Who Tasted Shapes,' heightened synesthesia's prominence and prompted psychologists and neuroscientists to examine the condition experimentally.

Synesthesia Live Visual Software Studio

In 1987, a team led by Baron-Cohen found the first hard evidence that synesthetes' experiences are consistent across time. The researchers asked a synesthete to describe the color that each of 100 words triggered. A year later, they repeated the test without warning and found that the associations between words and colors that their subject described were consistent with her initial responses more than 90 percent of the time. In contrast, people without synesthesia, asked to perform the same task but with only a two-week interval between the two tests, were consistent only 20 percent of the time.

In later research, Baron-Cohen's group established that synesthesia is not only consistent across time but also concretely measurable in the brain. Using positron-emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging, the researchers have found that for synesthetes who report colored hearing, visual areas of the brain show increased activation in response to sound. That isn't the case for nonsynesthetes.

Other studies have demonstrated that synesthetic perception occurs involuntarily and interferes with ordinary perception. And last summer, University of Waterloo researchers Mike Dixon, PhD, Daniel Smilek, Cera Cudahy and Philip Merikle, PhD, showed that, for one synesthete, the color experiences associated with digits could be induced even if the digits themselves were never presented. These researchers presented a synesthete with simple arithmetic problems such as '5 + 2.' Their experiment showed that solving this arithmetic problem activated the concept of 7, leading their synesthete to perceive the color associated with 7.

This finding, published last July in the journal Nature (Vol. 406), was, according to Dixon, the first objective evidence that synesthetic experiences could be elicited by activating only the concepts of digits. As such, these results suggest that, at least for this synesthete, the color experiences were associated with the digit's meaning, not just its form.

Together, the evidence shows that 'something is going on in the sensory areas of the brain,' concludes Christopher Lovelace, PhD, a research fellow at Wake Forest University School of Medicine. 'What we have to do now is try to figure out how the brain does it.'

Uncertain origin

A century ago, researchers ascribed synesthesia, somewhat vaguely, to 'crossed wires' in the brain. Today, despite neuroscientists' more complex understanding of brain anatomy and their sophisticated tools for tracking brain function, synesthesia's roots continue to elude understanding. Several competing theories have emerged, but all require further testing. Latest apple mac update.

Baron-Cohen and his colleagues propose that synesthesia results from a genetically driven overabundance of neural connections in the brain. Ordinarily, Baron-Cohen explains, different sensory functions are assigned to separate modules in the brain, with limited communication between them. In synesthesia, Baron-Cohen and his colleagues posit, the brain's architecture is different. Synesthetes' brains, they believe, are equipped with more connections between neurons, causing the usual modularity to break down and giving rise to synesthesia.

Daphne Maurer, PhD, a psychologist at McMaster University, has further speculated that all humans may be born with the neural connections that allow synesthesia, but that most of us lose those connections as we grow.

Naropa University psychologist Peter Grossenbacher, PhD, agrees that there's likely a genetic root to synesthesia, and like Baron-Cohen's group, he and his colleagues have teamed with molecular geneticists to probe the question. But Grossenbacher and his colleagues suspect a different brain mechanism.

'We don't need to posit some abnormal architecture of connections in order to account for synesthesia,' Grossenbacher argues.

Instead, he proposes that in the brains of synesthetes, 'feed-backward' connections that carry information from high-level multisensory areas of the brain back to single-sense areas are not properly inhibited. Ordinarily, information processed in such multisensory areas is allowed to return only to its appropriate single-sense area. But in synesthetes' brains, Grossenbacher argues, that inhibition is disrupted somehow, allowing the different senses to become jumbled.

Grossenbacher believes his view is consistent with the fact that hallucinogenic drugs can temporarily induce synesthesia.

'I don't think that new connections are forming in the brains of those individuals for a few hours and then disappearing,' he says. 'What's much more sensible is that existing connections become used in a way that's neurochemically altered for a few hours.'

But, Grossenbacher acknowledges, 'The trouble with theorizing in this area is that we're underconstrained by data. There isn't the right kind of data, yet, to differentiate between these different theories.'

Baron-Cohen agrees, 'Neuroimaging is the best thing we've got at the moment, but the spatial resolution isn't good enough to allow us to see whether the individual connections in the brain are cross-wired.'

Post-mortem examinations would allow closer inspection of what's different about synesthetes' brains, Grossenbacher and Baron-Cohen agree. But, so far, no known synesthetes have died and left their brains to science.

Implications

For psychologists, interest in synesthesia extends far beyond just the study of the few individuals who experience the phenomenon.

'Synesthesia taps into a lot of other domains that are more familiar to many psychologists,' says Marks. 'It tells us something about the nature of perception and what makes things perceptually similar to one another. Video editing software free. download full version no watermark. Synesthesia may help us to understand how the concept of similarity is embedded within the nervous system.'

In addition, Dixon suggests, the fact that synesthetic perception interferes with the perception of physical stimuli highlights an important aspect of cognition.

'We tend to think of our experiences, and especially the visual system, as being bottom-up,' he remarks. 'But there are many instances where meaning goes back down and influences our lower-order perception of the world. Synesthesia is just one very rare and exceptional example of that.'

The possibility that synesthesia has genetic roots is equally tantalizing, says Grossenbacher--especially if it turns out that a single gene controls the condition, as some have speculated.

'If indeed something as central to mental life as [synesthesia] is controlled by a single gene, this might be rather a new kind of gene to know about,' says Grossenbacher. 'It would be a gene that, in either of its forms, results in a healthy human but has a profound effect on the organization of the nervous system.'

At a practical level, many researchers observe, research on synesthesia will help raise the condition's visibility, reducing the risk that clinicians might mistake it as a sign of mental illness.

In addition, Grossenbacher, Lovelace and Crane--who conducts research on synesthesia while completing her doctorate in clinical psychology--are beginning to examine whether common mechanisms might underlie both synesthesia and hallucination. If so, synesthesia may be an ideal laboratory for studying those mechanisms.

'This is a group of people who would be available for research,' explains Crane. 'Unlike patients who experience hallucinations, synesthetes are not medicated, so you don't have that confounding factor. We're able to talk about our experiences. We offer something very valuable.'

Further Reading

Cytowic, R.E. (1993). The man who tasted shapes. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Grossenbacher, P.G., & Lovelace, C.T. (2001). Mechanisms of synesthesia: Cognitive and physiological constraints. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5 (1), 36-41.

Harrison, J.E., & Baron-Cohen, S. (Eds.) (1996). Synaesthesia: Classic and contemporary readings. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

The Web site for the International Synaesthesia Association can be found at www.psychiatry.cam.ac.uk/isa/.

Thanks for letting us know that this page . Mojave requirements macbook air.

Thank you for your feedback. How could we improve this content? Thank you for your feedback.